[Updated November 1, 2015 with information from Dictionary of Artists’ Models by Jill Berk Jiminez]

After all the “spin” and “strangeness” of the last days, time for a bit of charm.

While I’m primarily a words-numbers-and-music kind of guy, I do have visual arts preferences. One painter that has always had a very special place in my heart happens to be

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841-1919). Renoir is usually pigeonholed as an impressionist, but in truth his work ranges from the impressionistic to the classically figurative.

This post is inspired by Sarah Hoyt’s post on PJMedia about appreciating the female form — something Renoir was one of the greatest masters in history of. Aside from the many commissioned portraits of women and young girls he painted, below are the brief stories of his principal models, muses, and “women in his life”.

Click “more” for the whole article. “Trigger warning”: some tasteful, exquisitely artistic, female nude paintings.

The women of Renoir

Lise Tréhot

She was his first muse, associated with his early “Salon period”. Below she appears in the early painting “In Summer”:

The painting that first gained Renoir professional recognition, “Lise with the umbrella” (1867) with its unique shade effects, likewise features her.

She also posed nude for him, e.g., in “Diana” below:

The two apparently became lovers, and at one point the couple moved in with Renoir’s parents (see http://www.artistsandart.org/2009/09/renoir-and-his-models-lise-trehot.html ). Lise gave birth to a daughter, Jeanne: Renoir did not officially recognize Jeanne as his daughter, but his name appears on the baptismal certificate. Jeanne was placed in the care of a wet-nurse to raise her as her own child. Via one of his art dealers, he secretly supported Jeanne financially until his dying day, and is said to have made arrangements for this to continue beyond the grave.

After a separation caused by Renoir’s conscription into the French army during the 1870-1 Franco-Prussian War, things apparently weren’t the same again: According to the German wikipedia [

caveat lector] article here (

http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Im_Sommer), she broke up with Renoir in 1872 to marry an architect named Georges Brière de l’Isle, said her bohemian lifestyle farewell, and never modeled for anybody again. Shortly before her death, she is

said to have destroyed many of her personal papers related to Renoir. He himself never mentioned her later.

Marguerite Legrand (“Margot”)

Renoir tried to court the daughter of a well-to-do family, but they (the Le Coeurs) nixed the marriage because they thought the not-yet-famous painter was a poor prospect as a provider. (Renoir’s emerging reputation had yet to translate into financial security.)

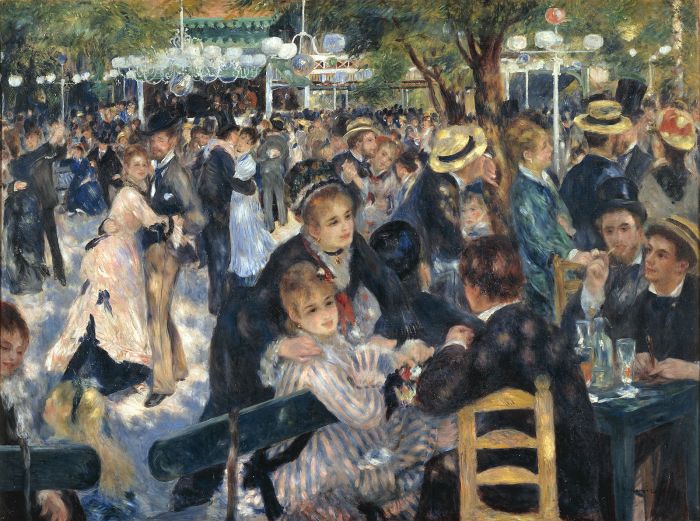

Apparently she died suddenly of smallpox a short while later. Renoir is said to have nursed her until the end, and to have paid for her funeral. She appears on the left in one of Renoir’s most famous canvases, the 1876 “Bal du moulin de La Galette” (see also here ; note the light-speckling effect in this painting as well.)

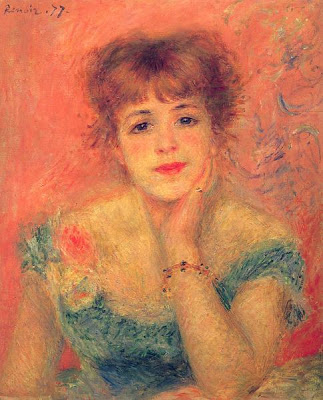

Jeanne Samary

Aline Charigot (later Aline Renoir)

Renoir used to shop at a dairy store for cheeses and the like. There he met a dressmaker 20 years his junior named Aline Charigot. The plump, vivacious strawberry blonde (Venetian blonde, in painter’s lingo) appears to have epitomized Renoir’s idea of female beauty, and she was to appear countless times in his work. Uniquely among Renoir’s models, she spans three out of his four creative periods: “impressionist”, the neo-figurative “dry style” or “Ingresque style” (roughly 1882-1888), and the “pearly style” (1888 until his death) in which he sought a synthesis of impressionist and classicist elements.

As was Renoir’s apparent wont with his models, he would change Aline’s hair color to fit the painting’s general composition. Below she is portrayed facing Renoir himself:

Renoir painted this nude of her, “Blonde Bather”, from memory when he was away in Italy to study the art of the Italian masters, particularly Raphael and Titian.

This trip would mark Renoir’s departure from Impressionism — which he by then perceived as a dead end (“I discovered I couldn’t paint or draw anymore”) — towards the more classically figurative “style aigre” (literally “sour style”, more idiomatically “dry style”). Below is an early “style aigre” painting featuring Aline, “By the seashore” (1883), one of my favorite Renoirs.

Below are just two more of many paintings Aline appears in.

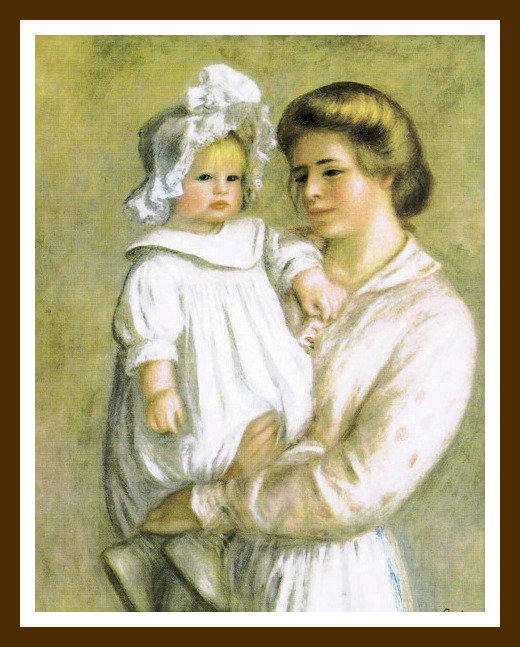

In “Motherhood”, she is breastfeeding their eldest son, the future actor

Pierre Renoir (1885-1952).

The couple cohabited 1880-1890, then had a marriage that lasted until her death in 1915. She would bear him two more sons:

Jean Renoir (1894-1979, to become the leading French movie director of his generation) and Claude Renoir (1901-1969, not to be confused with

Pierre’s eponymous son). Since Claude’s birth, she suffered from diabetes: this appears to have been the root cause of her early demise in 1915, even as the proximate cause of her death was a heart attack. Below is Renoir’s portrait of Aline Renoir in her premature old age (1910):

Suzanne Valadon

Renoir worked all of three years — the longest of any of his paintings — on “The Large Bathers” below (over twenty studies for this masterpiece have been preserved — the original can be viewed in Philadelphia).

“Portrait of Suzanne Valadon” by Renoir (again, with a hair color change):

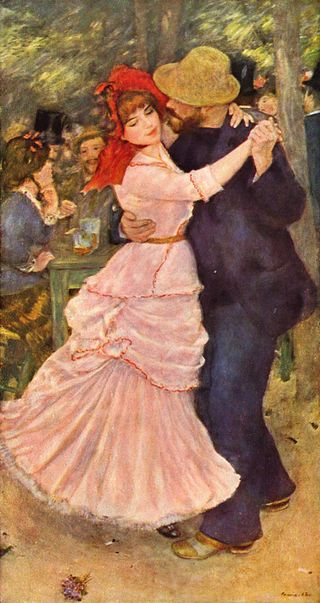

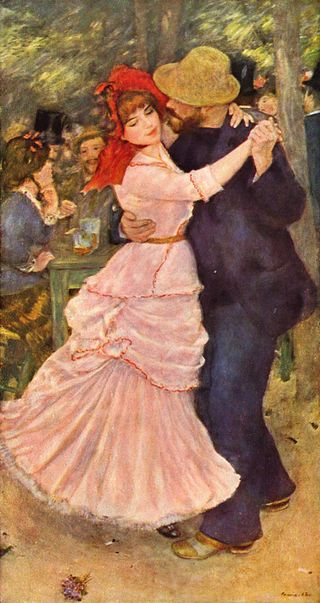

Dance at Bougival (1883):

The petite (1.54m, or five foot and 2/3 of an inch) Suzanne originally was an aspiring circus acrobat, but after a fall from the trapeze ended that career, she made ends meet as a painter’s model for artists ranging from Renoir to Toulouse-Lautrec to Degas. She had a very “bohemian” love life and apparently slept (among others) with all three painters. In 1883 she gave birth to a son who was to become the well-known cityscape painter

Maurice Utrillo. One of her then-boyfriends, the young painter Miguel Utrillo, had recognized the son as his, even as he was well-aware that both Renoir and Degas could have been the biological father. Miguel is said to have quipped “I’d be glad to sign my name on a Renoir or a Degas any day”.

She did not just model for, and sleep with, artists, but learned from their techniques. After Degas saw her sketches, he took her under his wing and nurtured her career as an artist in her own right. In 1894, Valadon became the first-ever woman painter admitted to the

Société Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

In 1893 she had a brief (six months) but stormy affair with the eccentric and reclusive composer

Erik Satie. Quoting Wikipedia:

After their first night together, he proposed marriage. The two did not marry, but Valadon moved to a room next to Satie’s at the

Rue Cortot. Satie became obsessed with her, calling her his

Biqui, and writing impassioned notes about “her whole being, lovely eyes, gentle hands, and tiny feet”. During their relationship, Satie composed the

Danses gothiques as a kind of prayer to restore peace of mind, and Valadon painted a portrait of Satie, which she gave to him. After six months she moved away, leaving Satie broken-hearted. Afterwards, he said that he was left with “nothing but an icy loneliness that fills the head with emptiness and the heart with sadness”.

[12] It is believed this was the only intimate relationship Satie ever had.

[13]

In 1895 she married a stockbroker named Paul Moussis and became a full-time painter. That marriage fell apart when in 1909 Suzanne became a pioneering “cougar”: at age 44 she began an affair with a painter young enough to be her son (André Utter, age 23). The May-December couple married in 1914 and divorced in 1934, four years before her death in 1938.

Gabrielle Renard

The negative critical response to The Large Bathers caused Renoir to reconsider his style, and revisit impressionistic color and light effects while retaining some of the figurative aspects. This new synthesis, “style nacrée” (pearly style), dominated his work until his death.

Gabrielle appears to have been utterly devoted to Jean for the rest of her life, the relationship being not so much that between a caregiver and her charge, as that between surrogate mother and son. Jean Renoir’s autobiography,

My Life and My Films, starts and ends with Gabrielle, and throughout refers to the profound influence she had on him. (In contrast, his references to his biological mother Aline are almost perfunctory: her role in his life appears to have been more that of a standoffish disciplinarian.) Gabrielle would actually introduce Jean to his future profession at a very young age, when she took him to see an early moving picture [see, e.g.,

here].

“Surrogate mother” and child are depicted together here:

In the family portrait by Renoir below, we see, left to right: Pierre Renoir, Aline Renoir, Jean Renoir, and Gabrielle Renard. The “mystery girl” on the far right appears to have been Marie Izambard, daughter of rhetorics professor and journalist Georges Izambard (onetime neighbor of Renoir)

Gabrielle (who had grown up on a farm and could work very well with her hands) eventually became Renoir’s chief assistant: he would become ever more dependent on her because of crippling rheumatoid arthritis. In fact, paintbrushes would eventually need to be tied to his hands as he could no longer hold them. That he still, in that state, turned out a steady stream of work testifies to both to his artistic genius and to his drive.

According to

Jiminez, p. 452, Gabrielle was very well liked because of her good-natured personality, had a hearty appetite in food and drink, and on one occasion got a diamond ring from an anonymous admirer. Sometime in 1913 (Jiminez, q.v.; see also

http://www.alazraki.com/artists/Renoirtete.html ), Aline Renoir became increasingly jealous of Gabrielle’s attachment to the aging painter, and she was expelled from the household in December 1913. After Aline’s death, Gabrielle returned to the Renoir estate and again become the painter’s assistant, but no further paintings with her as model have been preserved.

She would marry a rich expatriate American painter in 1921 but maintained very close relations with her quasi-adoptive son Jean Renoir until her dying day. The final sentence of Jean’s autobiography is in fact: “Wait for me, Gabrielle!”

One of Renoir’s less well-known gems, an early example of the “pearly style”, is the (to me) breath-taking

La baigneuse dormante (

The Sleeping Bather , 1897). The

Dutch wikipedia article claims the Gabrielle was the model: while she has red hair in the painting, Renoir may have changed her hair color to fit the reddish-hued composition. Let the painting speak for itself:

Renée Jolivet

She was the daughter of the midwife who delivered the youngest son, Claude Renoir (1901-1969), and was promptly hired to be his nanny. Renée also was painted by Renoir a few times: below she and Claude appear together.

An article in LIFE magazine, July 5, 1937, shows her in front of two paintings she posed for:

This is the second painting:

Madeleine Bruno

In LIFE magazine, July 5, 1937, she is described as a vegetable seller in Cagnes-sur-mer who also posed for Renoir. Some Googling turned up this painting being auctioned by Christie’s http://www.christies.com/lotfinder/paintings/pierre-auguste-renoir-tete-de-madeleine-5554030-details.aspx

Quoting from the “lot notes”

Renoir has here portrayed Madeleine Bruno, a local village girl who began modeling for him in the early 1910s. It was in 1913 that the artist was forced to dismiss Gabrielle Renard, his favorite model and studio assistant since 1895, because of increasing friction with his wife Aline. Madeleine soon became a member of his household at Les Collettes in Cagnes. She is featured in a pair of important bather paintings, both entitled Baigneuse assise, done in 1913 and 1914 (the latter in the Art Institute of Chicago). In early 1915 she was joined by another girl, 16-year-old Andrée Heuchling, who affectionately became known to the artist’s family as Dédée. Madeleine posed for the standing nude in the foreground in Deux baigneuses, 1916, while Renoir placed the partially clad and seated figure of Dédée behind her. In Le concert, 1919 (The Art Gallery of Ontario, Toronto), Renoir depicted Madeleine listening while Dédée played the mandolin. The two young women were the models in Renoir’s final masterwork, Grande baigneuses, 1918-1919 (Musée d’Orsay, Paris), his paean to peace in celebration of the end of the First World War.

The 1914 Baigneuse assise (seated bather):

Catherine Hessling (a.k.a. Andrée Madeleine Heuschling), nicknamed “Dedée”

During WW I, this girl had sought refuge in Nice. There, she came to the attention of the painter Matisse, who thought she would make a great subject for Renoir and referred her to him. “Dedée” was his last model (both clothed and nude): below she is depicted clothed. The movie

Renoir (

IMDB entry) is loosely based on her years with the painter and his son at

Cagnes-sur-mer, a suburb of Nice on the Côte d’Azur where the increasingly frail Renoir had moved for the mild climate.

Jean Renoir (recovering from war wounds at his father’s house) fell in love with her. They married in 1920: she starred in several of his early movies (

IMDB listing).

Les baigneuses (1918-1919), featuring both Madeleine Bruno and Catherine Hessling. One of the master’s very last works, painted in celebration of the end of World War I.

Le concert (1919), again featuring both Madeleine and Dedée:

Let me give the final words to Renoir himself:

Pour moi, un tableau doit être une chose aimable, joyeuse et jolie, oui jolie ! Il y a assez de choses embêtantes dans la vie pour que nous n’en fabriquions pas encore d’autres.

For me, a painting should be something likable, joyous, and pretty, yes pretty! There are enough annoying things in life, that we need not create still more.

(Pierre-Auguste Renoir, quoted in Albert André, Renoir, 1923)

Ce dessin m’a pris cinq minutes, mais j’ai mis soixante ans pour y arriver.

This drawing took me five minutes, but I put in sixty years to get to that point.

Thanks for highlighting the true contributors to Renoir’s fame.Hurrah to

These unsung great ladies who contributed to the making of these great

Paintings.The French academy should honour them for their contribution,

By. Their sacrifices and hence forth fix a proper remuneration to future

Painters models (approximately 10%) of the first and subsequent sales

Proceeds.I hope it will be an honourable thing to do.

[…] The women of Renoir: models, muses, and partners […]

[…] one hand, I do not consider artistic, tasteful classical nude paintings to be offensive at all and have even written a long blog post about Renoir’s models. On the other hand, know your audience: it would not occur to me to display this type of painting […]

I have heard the story of Renoir’s model that he met on aParis street with her mother and he asked for permission to use her as a model for his painting ” Moulin de la Galette” . She was sad and not suitable as his centre piece girl . When he discovered that in sitting for him she was unable to see her boyfriend on that day which is why she was sad. He changed the day for his sitting and she came “alive” again and he was more than satisfied by her appearance then. Any one else know of this tale?